A row of Austrian pines borders the construction site for the new Siebel Center for Design, their weathered branches softening the modern lines of the stone and glass building.

Rooted in the university’s early history, these century-old trees have been carefully preserved through the 18-month construction project that is set to wrap up this fall.

They are remnants of a wind break that protected a vast experimental orchard planted there in the late 19th century by botanist Thomas Jonathan Burrill, a pioneer in plant pathology and the third University of Illinois President (1891-94).

More broadly, Burrill is credited with beautifying the young agricultural campus through a comprehensive planting program, some of which survives today. Early university correspondence indicates Burrill personally planted most if not all of the trees on campus during the 1870s, University Landscape Architect Brent Lewis said. Before that, trees were scarce on the prairie landscape.

“He is the one who said, ‘This campus needs to look better,’ and then set about tree planting on a massive scale,” Lewis said. The 1870 annual report to the Board of Trustees noted that 3,000 apple trees had been planted and another 143,000 trees ordered for an arboretum, shelter belts and forestry tracts.

While serving as the first Dean of the College of Agriculture, Burrill was also the first resident of Mumford House, the oldest building on campus. Later he created the land-grant university’s tenure system and sabbatical leaves, and he organized the first campus master planning effort.

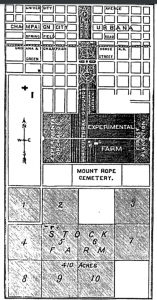

The Austrian pines sit on what planners refer to as the campus “military axis,” once a mile-long open space stretching east to west, from Lincoln Avenue in Urbana to First Street in Champaign. Early on it included the orchard, a large experimental farm, horticulture plots, and “The Forestry” now known as Illini Grove.

Given that rich history, Lewis didn’t hesitate to step in to save the trees during the planning for the Siebel Center. He has authority to review landscaping plans for construction projects and persuaded architects to build around the trees.

“As the protector of campus open space, I did not want to see them take down historic trees,” he said. “Just as the coronavirus is actively reminding us, our open spaces are just as valuable as our building spaces.”

The building’s architects weren’t thrilled, given that the trees are close together and admittedly “awkward. They’re not beautiful specimens,” Lewis said. But the project landscape architects rallied around the idea and supported him. The decision had no impact on the cost of the $48 million project.

The trees are important both aesthetically and historically, Lewis said: “You cannot take out trees that were planted by Thomas Burrill. Let’s remember our history. When people come to a campus, they want grandeur and a sense of place and history. They don’t want it to look like a strip mall with 2- or 3-inch trees in a planting island. They want to be wowed a little and know that we have been around a long time. They want to feel rooted in tradition, and old trees are our connection to the past.”

Overview of campus in 1871, showing the layout of the grounds as proposed in 1868. At center is the experimental orchard where the Siebel Center for Design is now under construction. Source: University Library, “Historical Campus Landscaping” by Douglas Chien

Lewis dates the pines back at least 91 years, to 1929, when they appeared on a landscaping plan. But he thinks they’re much older, based on their size and other trees in the area. A nearby Austrian pine taken out just before the Siebel Center construction started was likely 120 years old, he said. Others date back to the original planting in the 1870s, including one with a 32-inch trunk near Fourth Street and Gregory Drive. The five trees near Siebel Center have smaller trunks — ranging from 16 to 24 inches — but “when you plant them close together they don’t grow as big,” Lewis said.

Plans for the experimental orchard were launched soon after the university’s founding in 1867. Once planted, the rows and rows of fruit trees were protected by a wind break of Norway spruce and Austrian pines — which also helped keep out four-legged intruders.

“The cows kept going in and grazing on the research land. It was obviously a sore spot when you read some of the old correspondence about it,” Lewis said.

Most of the trees eventually died or were cut down — one by one or en masse when the orchard was removed around the time of World War I, he said.

At that point the land transitioned from agricultural science to military science, Campus Historic Preservation Officer Dennis Craig said. Barracks and horse stables were built for military drills with cannons and armored caissons. The nearby Armory was constructed in the early 1920s, and the area became known as the military axis. The western edge of the axis, now filled with residence halls, was once used for military parades — which is how WPGU radio got its call letters. The station originally broadcast from a building on the Parade Grounds Unit (and later the basement of Weston Hall), Craig said.

Over the years, the military axis filled in with buildings, starting with McKinley Health Center in the late 1920s — and later, Lincoln Avenue Residence (LAR) Hall in the 1940s, Champaign residence halls and Allen Hall in the ’40s and ’50s, and agricultural, art and education buildings from the ’60s on. But a smattering of trees survived.

The forest tract, now Illini Grove, used to extend all the way up Lincoln Avenue to Nevada Street, where McKinley and LAR now sit. Burrill kept meticulous records with sketches showing which species were planted where, Craig said. Some of the original trees remain around those buildings as well as the Child Development Laboratory and Department of Dance studio on Nevada.

Until recently, the Siebel Center had seven surviving Austrian pines — six clustered together and one closer to Huff Hall at the corner of the construction site. “We lost the one at the corner right as we started to design this project. It was unfortunately the best specimen,” Lewis said.

Another died soon after construction started, and now one of the five survivors is looking ragged. The suspect? Diplodia blight, a common disease for Austrian pines. The construction wear and tear doesn’t help, Lewis said.

Saving the trees is more important than ever, he said. The campus has lost more than 11 percent of its trees in the last 10-15 years, from climate change and a campus construction boom.

“All of our old trees are dying at a fairly rapid pace,” he said. “What we’re losing are the large ones with the bigger canopies. When we do put new ones in, they’re young and very small. The net effect is an exponential deficit in the environmental benefit of the trees.”

When possible, Lewis has offered up trunks from old trees for reuse, which have made their way into student and faculty projects over time. “Anything we can do to hold onto a piece of history is better than the alternative of chipping them for campus mulch,” he said.

Beyond aesthetics, the trees are “a link to the past and history of this university that I think we should cherish as long as we have them,” Craig said.

— Article and photos by iSEE Communications Specialist Julie Wurth