The University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign is well past the halfway point from Illinois Climate Action Plan 2020 to iCAP 2025. It’s time to check in on each of the iCAP chapters to gauge progress, address the challenges our campus faces, and celebrate some achievements. This month, iSEE Communications Intern Gabe Lareau examines the Transportation chapter to see if the university is on the road to fully sustainable transport by 2050. View the full series >>>

Bicyclists check in near the Alma Mater on Bike to Work Day 2022. Credit: Mark Herman/iSEE Communications

America’s overuse of the internal combustion engine has resulted in one of the most visual reminders we have of our reliance on fossil fuels: the automobile, with its inescapable “honking, skidding, speeding, sputtering, and backfiring” and “emission of toxic fumes and filthy exhaust-pollution,” as eloquently described in The French Dispatch.

Is it possible to break this addiction? What will transportation of the future look like? Many have offered their fair share of outlandish ideas, like Walt Disney’s beloved monorail, the flying cars in Back to the Future 2, or Jean-Marc Coté’s early 20th century drawing of … a whale-bus?

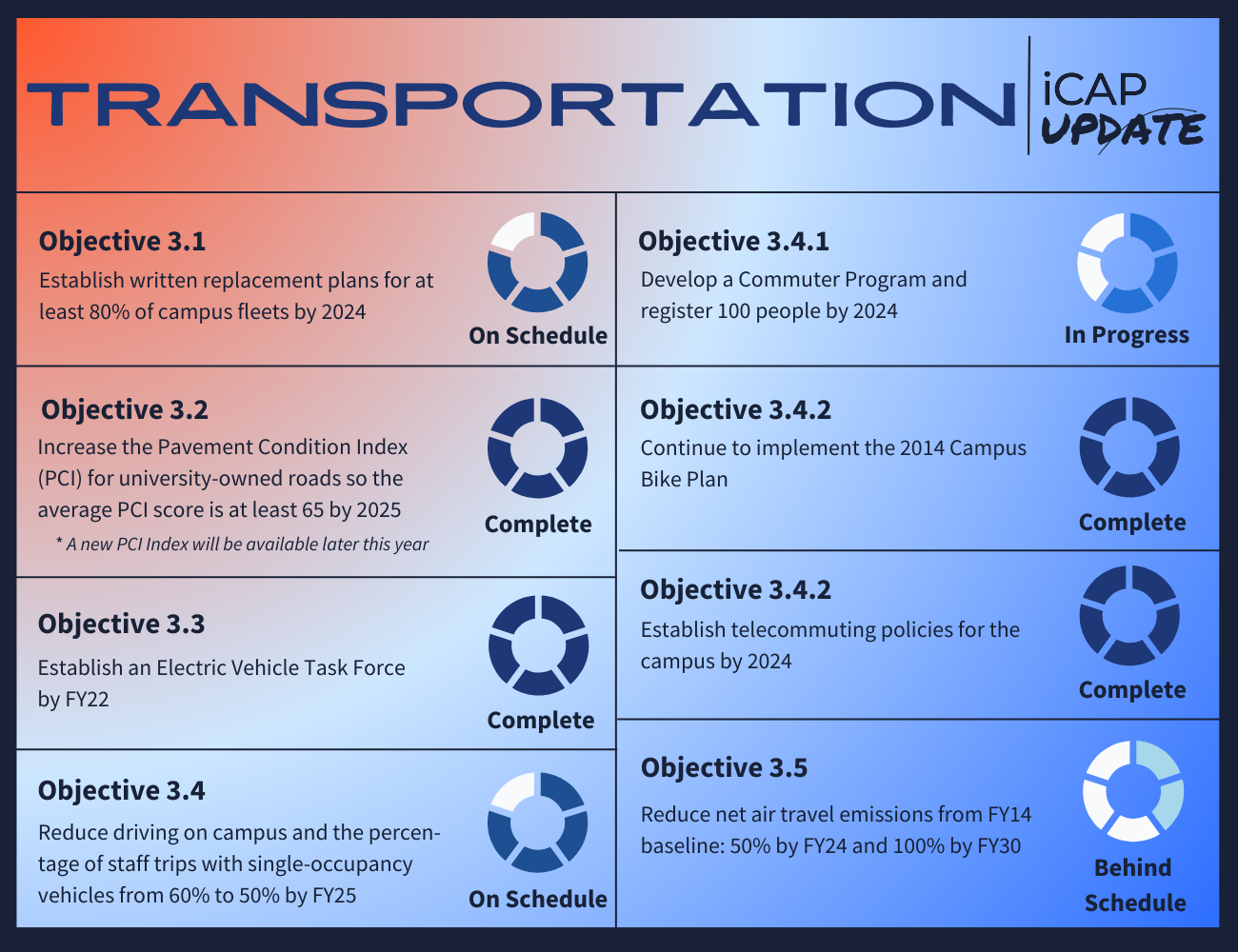

Campus has had great success fulfilling its Transportation objectives by laying the groundwork for 80% of campus fleets to be electric, drastically reducing staff single-occupancy vehicle trips, and continuing to implement the 2015 Campus Bike Plan. But big challenges remain — in particular, standardizing a campus-wide carbon offset policy to negate emissions from air travel.

Whether high-speed rail or high-speed whale, the future of transportation will have to be more sustainable. In 2021, every single mode of transportation in the United States, from Navy aircraft carriers to amusement park go-karts, contributed 1,775 million metric tons of CO2 equivalents to the atmosphere. That makes up 28% of overall U.S. emissions and represents the largest contribution from any one economic sector.

The urgency of this issue, and the important part it will play in getting the University of Illinois to net zero carbon by 2050, is not lost on the Transportation iCAP Topical Team. Since 2020, the team has seen progress on some of its biggest tasks — planning to electrify the campus fleet, which has already significantly reduced emissions due to fewer trips taken in more efficient vehicles; establishing an Electric Vehicle Task Force; and continuing implementation of the 2014 Campus Bike Plan among them.

But because “transportation” is so broad a topic, there are still a few bumps in the road. This mostly involves the copious amounts of emissions generated from air travel. To make that more sustainable, or any other form of transportation for that matter, the university community has three choices available.

First, campus can upgrade its equipment and infrastructure to decrease carbon emissions, like the iCAP objective of developing written plans to electrify 80% of campus’ fleets. Second, individuals can switch to low- or zero-carbon commuting alternatives by choosing to carpool, walk, ride a bicycle, or take mass transit. If neither of the first two “active transportation” options are feasible, then the university must negate the carbon it generates by purchasing responsibly sourced offsets. That’s especially true for air travel, as widespread sustainable aviation is decades off and biking across the country is out of the question save for a strong few.

To make campus transportation fully sustainable by 2050, the U of I will need to do a combination of all three.

In terms of upgrading equipment, electric vehicles (EVs) have surged in popularity nationwide as well as around the world, for a variety of reasons. Their range has steadily increased, and because they run on lithium-ion battery power they present a lower- or zero-carbon way to get around compared to traditional cars, depending on if the battery was charged by renewable energy.

Facilities & Services, which operates hundreds of trucks and cars, has introduced a few EVs and hybrid vehicles into its carpool; it also has a sustainable fleet plan aimed at reducing fuel usage and vehicles and introducing new technologies.

The iCAP prescribes that, by the end of this year, the university should have “written replacement plans for 80% of campus fleets” and that an Electric Vehicle Task Force should be well underway in exploring all options relating to EVs and charging stations for campus. These two objectives have been among the Transportation Team’s top priorities this past year, according to Chair Sarthak Prasad, Sustainable Transportation Assistant at F&S.

“During Fall 2023, we were mainly focusing on the fleet replacement plan that we had worked on in May,” Prasad said. “Since then, that recommendation was approved.”

In that recommendation are two preliminary but vital steps of establishing what exactly a “fleet” is, then establishing a “point of contact” for each fleet.

Deciding on what constitutes a “fleet” is kind of like determining the difference between a really big puddle and a small lake. Units like F&S or the Division of Intercollegiate Athletics (DIA) have large numbers of vehicles. But “there are departments that have one or two vehicles that are assigned to a certain researcher or a lab group,” Prasad said. Will those few internal combustion engines get a free pass because they’re not part of a larger group of vehicles?

Whatever the verdict, the next step will be asking each department to designate an existing employee to take on the responsibilities of a “fleet administrator.” Fleet administrators will coordinate with F&S to develop replacement plans with more sustainable options, like hybrids or EVs. Once a point of contact is established, “then communication will be much more efficient and coherent,” Prasad said.

An electric car is charged in a campus parking garage. Credit: Gabe Lareau

Once all of these electric vehicles hit campus, they obviously will need to be charged. Currently, campus has 18 individual charging stations across six locations. Many, many more will be needed once EVs inevitably overtake the university district’s streets. That is why, in 2022, the Electric Vehicle Task Force — operated by the University Parking Department — contracted a third party to conduct an analysis for possible EV infrastructure on campus.

For the rest of the campus community, individuals with the means can invest in an electric car, which may be eligible for a $7,500 federal tax credit and a state credit of up to $4,000. Others who can’t afford an EV can turn to alternative means of sustainable transportation.

This leads us to our second way of mitigating transportation emissions: changing individual habits. According to Prasad, the average commute distance for university faculty and staff is about 7 miles. While that would entail a 30-minute bike ride — perhaps daunting to many commuters — those who live 4 miles or fewer from campus are at an entirely bikeable distance, aided by Champaign County’s mercifully flat topography and the university’s excellent bicycling infrastructure.

That infrastructure didn’t become exemplary by simple happenstance. The Transportation Team has followed the recommendations of the 2014 campus bike plan and worked to improve it; an updated draft will be submitted by the end of Spring 2024, according to Prasad. Until then, the U of I renewed its “Silver” status as a Bicycle Friendly University from The League of American Bicyclists in 2023. However, “our goal for the next cycle will be gold,” Prasad said.

If you’re closer to the university than average, walking is always an option that is not only sustainable, but also alleviates stress. Nor should we forget our partners at the Champaign-Urbana Mass Transit District (MTD). The MTD not only has its own climate action plan, MTD2071, but also four hydrogen-fueled, zero-emission buses that multiply the immediate reduction in emissions that comes from using public transit. And don’t forget: Anyone with an I Card can ride the MTD free of charge.

If none of these are an option, whether due to disability or chronically sleeping in, some employees may still be able to cut down on commuting by working a hybrid or fully remote schedule. Nixing the commute is an easy way to reduce emissions and therefore make campus cleaner and greener — a win-win, especially for those who prefer to work in their pajamas.

The options for sustainable commutes — “Bus, Bike, and Hike” as they’re known in the iCAP — are integral to the Transportation Team’s Commuter Program. This initiative, aimed at reducing the number of parked cars on campus by asking commuters to relinquish their parking permits, was launched in 2023 and seeks to have 100 registered members by the end of this year.

According to Prasad, the pilot program saw mixed success, with opportunities for improvement: “What we saw during the pilot was people signing up who don’t have a parking permit. That’s not a bad thing because it’s celebrating those people who ride a bicycle or take the bus or walk to work. But the intent behind this program was to reduce the number of parking passes on campus, which unfortunately did not happen.”

The Commuter Program is an attempt to accelerate a larger trend. The number of faculty, staff, and students who commute to campus by driving alone has steadily decreased for nearly two decades. In 2007, the percentage was in the stratosphere at 74%. In 2011, it dropped to 65%; in 2019, 60%. In 2022, partially due to the effects of the pandemic, campus saw its biggest reduction over the shortest time — 55%. This figure sets campus up to meet its 50% goal by 2025.

Such a radical reduction is due to multiple factors. Since the late 2000s-early 2010s, campus bicycle and walking infrastructure quality has dramatically increased. But simple infrastructure can’t actually make anyone do anything; individual choices have compounded to bring about large reductions in driving on campus, and therefore large reductions in carbon emissions.

The largest of those carbon emissions, air travel, is unfortunately out of individual control. While, of course, no one commutes to campus daily via plane, university-related plane trips are a significant factor in campus’ contribution to global climate change. Air travel is most commonly used in three separate areas: study abroad programs, conference travel, and athletic games — a metric that is surely set to increase, as the Big Ten has now expanded to the West Coast.

The best way to reduce air travel emissions is, obviously, not to travel by air. The COVID-19 pandemic also made teleconferencing, a sustainable alternative, more mainstream. When taking an airplane is absolutely necessary, the only realistic option to travel sustainably is to purchase carbon offsets. iSEE has a webpage suggesting how to responsibly choose carbon offsets for individuals, but work toward a university-wide system has stalled, putting the iCAP’s goal of a 50% reduction by 2025 in serious jeopardy.

Until then, we will have to rely on individual choice to reduce air travel emissions — a mixed blessing. Mixed because rallying some 50,000 individuals to achieve a common goal is a daunting prospect. But it’s also a blessing because when we reach our targets — as campus is projected to do for total emissions in 2025 — anything becomes possible.