The University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign is already past the halfway point from Illinois Climate Action Plan 2020 to iCAP 2025. It’s time to check in with each of the iCAP topical chapters to gauge progress, address the challenges our campus faces, and celebrate some achievements. This month, iSEE Communications Intern Gabe Lareau examines the Resilience chapter to see how the university community is keeping up with its commitment to be climate-resilient. View the full series >>>

The Red Oak Rain Garden near Allen Hall is a shining example of both green infrastructure and biodiversity. Credit: Julie Wurth/iSEE Communications

Climate change often takes the future tense. In our international accords, nationwide legislation, and general discourse, we set sustainability goals with the implication that, if we do not succeed, the planet will be in for an environmental, ecological, and economic collapse.

Because of upgrades in community planning, the climate resilience of the Champaign-Urbana metro area is poised for big improvements in both stormwater and urban green infrastructure. The biggest hurdles lie ahead as the community must actually implement those infrastructural upgrades while also promoting green job programs and environmental justice initiatives. Graphic credit: Tori Lawlor/iSEE Communications

The conversation must now reflect the present. In recent years, extreme weather has become more commonplace — and more destructive. Oceans are rising and becoming more acidic. Wildfires are more frequent and burn longer, covering cities, like Champaign-Urbana last summer, in a blanket of haze.

The University of Illinois and its surrounding communities are and will be ever more affected. That’s why, in early 2019, representatives from Champaign, Urbana, Savoy, and the university formed the iCAP Resilience Team. This team is markedly different from other iCAP Teams. It is entwined with the community: Champaign, Urbana, Savoy, and other local entities are all involved in its efforts.

While the rest work away at reducing the U of I’s contributions to climate change — transitioning to renewables for the Energy Team, electrifying campus’ fleet for Transportation, etc. — the Resilience Team is preparing us for a more hazardous environmental future. Its mission is complex, interdisciplinary, unachievable without collaboration, and critical. By finding adaptation methods to minimize infrastructural or ecological damage due to the effects of climate change, the Resilience Team’s goals are deeply interwoven with the other iCAP teams’ efforts to mitigate further causes of climate change.

The 2020 iCAP identified three major areas that “augment our mitigation strategies with innovative resilience measures.” Those initiatives — rainwater management, urban biodiversity, and green jobs — each require an array of solutions. Because climate resilience presents a moving target that is hard to quantify, these approaches can seem unwieldy and even abstract. But these three areas are deeply interconnected.

Rainwater Management

While Champaign-Urbana isn’t affected by sea-level rise, flooding is still a risk. The most visible body of water here, the Boneyard Creek, is spanned by a bridge that takes three steps to cross, a timid non-factor whose biggest hazard is wet socks. But it wasn’t always this way.

A bicyclist navigates knee-high water on Green Street in Campustown on June 25, 1975, long before the city’s Boneyard Creek stormwater improvements. Photo courtesy Champaign County Archives

In the 1980s, the Boneyard would invade Green Street, submerging Campustown in knee-deep, pungent, destructive floodwater. This once-every-rainstorm event had an enormous negative impact on people’s livelihoods – flooding businesses, disrupting foot and vehicle traffic, and making its way into residences. Since 2002, when the city of Champaign launched its Streetscape project to divert the Boneyard into places like the Healey and 2nd Street basins, Green Street and its businesses and apartments have seen nary a drop of displaced water.

The Boneyard’s transformation from a perpetually imminent disaster to an issue the community hardly thinks about anymore is a local, effective example of what proper rainwater management can achieve. Its implementation has served a dual purpose: a drainage system for increased rainfalls and a prominent wildlife oasis in our increasingly drought-susceptible local climate. Since 2002, though, as the climate has grown hotter and more extreme weather events occur, both flood and heat risks have increased. More measures are needed.

Progress is being made through the Champaign County Stormwater Partnership, fulfilling part of the iCAP’s objective on the coordination of stormwater management across the C-U metropolitan area. A collaboration between the county, university, Champaign, Urbana, Savoy, and the Champaign County Soil and Water Conservation District (SWCD), the partnership provides resources on proper waterway management for industrial and residential uses. It also hosted the third Illinois Green Infrastructure & Erosion Control Conference in October.

Conferences like these further emphasize what the Resilience Team has recommended for this entire community: Upgrading rainwater management systems. Some of the best practices the team identified include an increased use of permeable pavement and native landscaping to minimize flooding. The recommendations have yet to be implemented and will likely require additional revenue — Urbana is set to increase its stormwater fees to $27 a month next year, and Champaign increased its fee by 3.5% last year.

Urban Biodiversity

While strengthening each community’s built infrastructure is certainly important, just as crucial for a resilient city is the capacity to support its natural infrastructure.

According to the Urban Biodiversity objective, not only do tree canopies “improve air quality and reduce atmospheric CO2,” they also “curb the heat island effect.” This is good news for not just the human residents of Champaign-Urbana, but also native bird and insect species that use them as habitats.

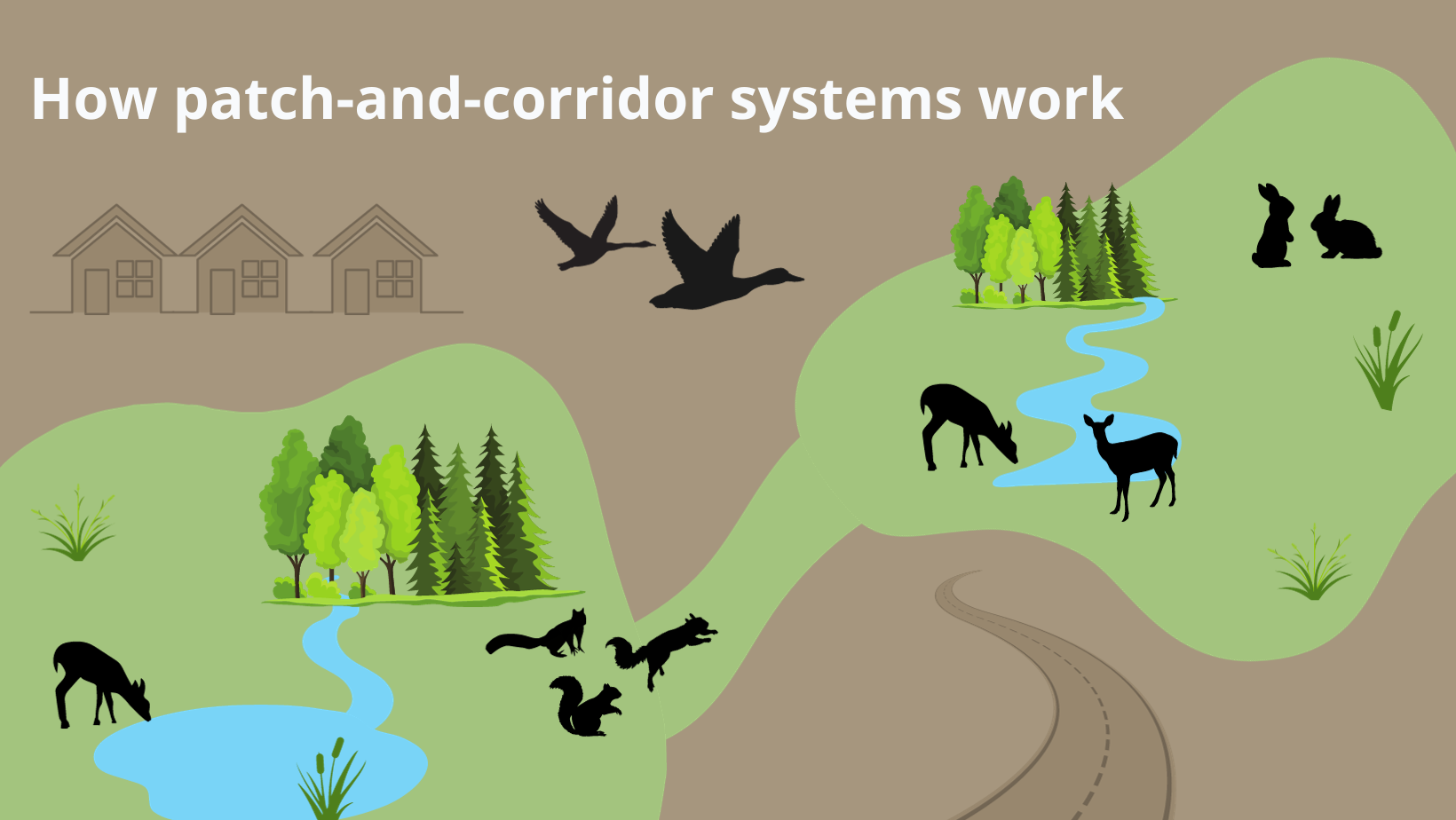

Wildlife can flourish in urban areas with the help of “patches” and corridors.” Species can move safely between different habitats (patches) through green corridors lined with native plants. This conserves native wildlife while also carrying all the benefits of green infrastructure. Graphic credit: Tori Lawlor/iSEE Communications

Trees also function as a natural water management system — they decrease stormwater runoff not only by taking up water but also by increasing water infiltration because their roots loosen the soil. The more there are, the more water their roots, and the newly absorptive soil, can soak up. Even more, trees also prevent soil erosion, a vital service to waterways choked by unwanted sediments.

Along with reducing stress by being more aesthetically pleasing than a concrete slab, natural shade can mitigate the urban greenhouse effect — a dire need in lower-income areas. According to Scott Tess, Urbana’s Sustainability & Resilience Officer and member of the iCAP Resilience Team, the city has been “reorienting” where to plant, placing about 100 trees per year in low-income and unshaded low-income areas in an effort to address locally the nationwide problem of poorer areas’ lack of tree cover. Using trees to help the most vulnerable and least fortunate among us also plays into the Green Jobs iCAP goal and completes a “tree-fecta” — absorbing water runoff, improving air quality, and promoting environmental justice.

The Resilience Team recommended that UI Extension develop an Urban Biodiversity Master Plan to make “the campus metro area a model for biodiversity.” While still a year from its planned completion date, the preliminary draft extensively catalogs the biodiversity assets, vulnerabilities, and possible improvements for Champaign, Urbana, and Savoy.

Its data-based conclusions — including C-U’s natural areas and their unique ability for flood management, the opportunities offered by new plantings for large-scale green job growth, and a rough patch-and-corridor habitat plan that would support pollinator and bird populations, among others — will guide the iCAP Resilience Team’s future efforts in this topic.

Green Jobs

Proper stormwater systems and biodiversity infrastructure do not simply appear out of thin air. Every iCAP Resilience objective will require a massive effort to recruit workers with a multitude of skills. Managing projects, conducting scientific studies, surveying ecosystems, actually building climate-resilient green infrastructure — all of these (and more) will be needed to fulfill the iCAP’s Green Jobs objective.

The City of Champaign is actively searching for a new employee to oversee its sustainability plan, the City’s version of the university’s iCAP. In Urbana, Tess has held his position for almost a decade and has overseen the city’s participation in Geothermal Urbana-Champaign and Solar Urbana-Champaign programs — as well as a solar landfill project. Tess also noted the many “exciting” legislative developments on the state and federal level — like the Inflation Reduction Act and Illinois’ Climate and Equitable Jobs Act — that could expand similar future programs.

In truth, every objective within the Resilience chapter (and, arguably, the entire iCAP) has the potential to spur job growth, especially among underprivileged communities and at-risk youths. For example, iSEE actively maintains a large list of interdisciplinary green job certification opportunities.

Another prospect for green jobs within the university metro area is laid out in the as-yet unpublished Urban Biodiversity Master Plan. To fulfill its short- and long-term goals of restoring Champaign-Urbana’s natural infrastructure as much as possible will require vast amounts of effort.

Nor will the iCAP-related job opportunities arise only within the community. The iCAP requires the University of Illinois to be a regional climate leader — a goal that our campus has partially fulfilled via its partnerships with other Big Ten institutions, the Illinois Geothermal Coalition, and more.

The path to resilient communities depends on the growth of green jobs and the proposition that reframing the issue from climate change to job growth can dampen backlash from climate skeptics. And, with programs mentioned in the iCAP like the National Green Infrastructure Certification Program (NGICP), which educates participants about the technical aspects and importance of their work, more people will realize that building resilient communities is a job-creating endeavor.

Perhaps soon, talking about our environment in the future tense might sound a little bit brighter.