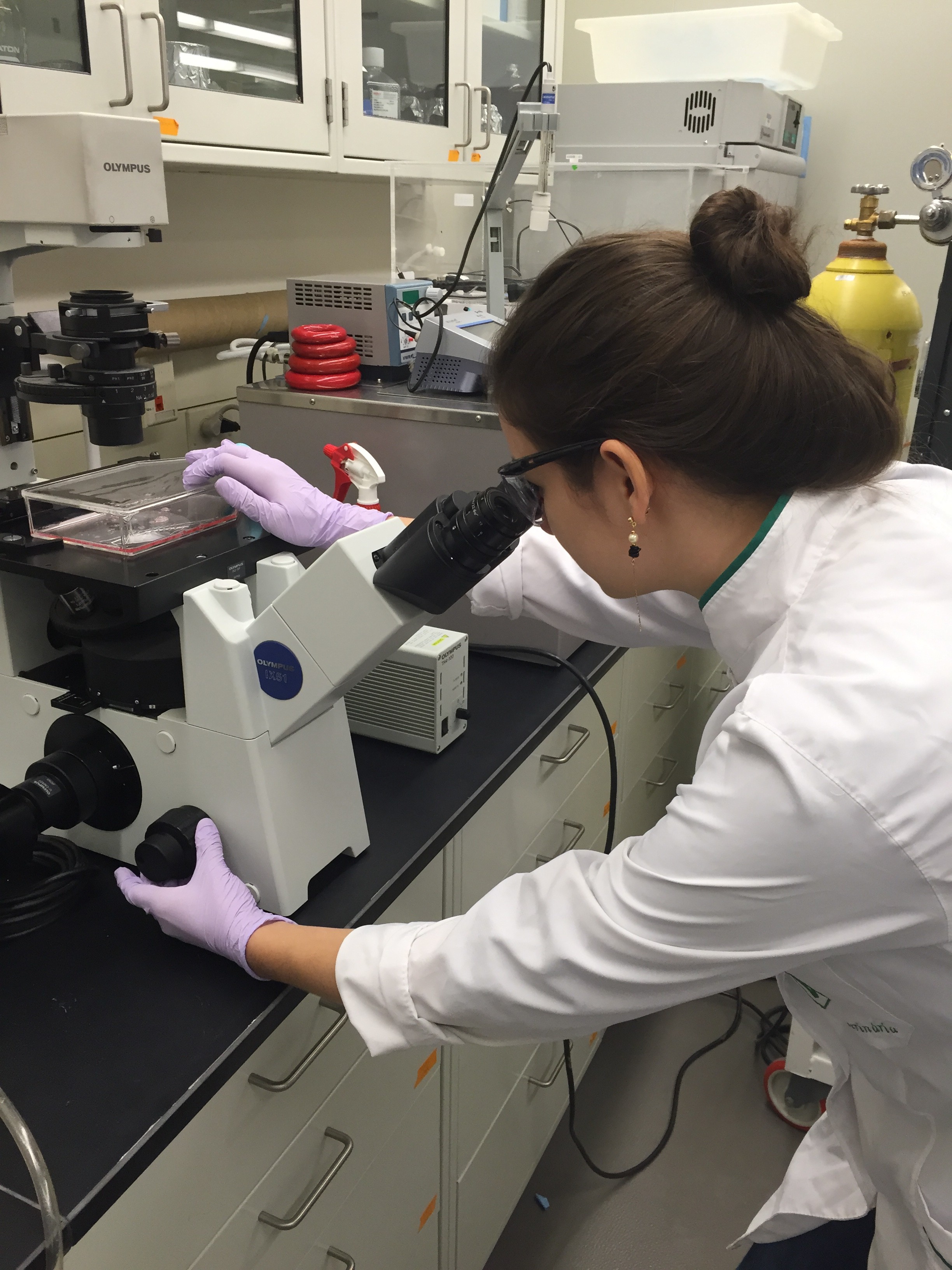

Kelley Goncalves is a Ph.D. student in Molecular and Cellular Biology, so her part in the Smart Water Disinfection project is mostly under the microscope.

Kelley Goncalves is a Ph.D. student in Molecular and Cellular Biology, so her part in the Smart Water Disinfection project is mostly under the microscope.

The Smart Water project as a whole seeks a more detailed understanding of how viruses become inactivated — noninfectious — after contact with common disinfection treatments, including ultraviolet light exposure and chlorine. A functioning virus enters a human cell, multiplies within the cell, and then spreads to surrounding cells. Inactivated viruses don’t make it to the spreading stage, so the host doesn’t get sick. Why? Kelley hopes to find out.

“What we do is we run the disinfection experiment at Newmark Civil Engineering Lab, and then we bring the samples to the microbiology lab for data analysis on damage to the virus’s complete set of DNA. We also do protein analysis — asking ‘what amino acids of the proteins are being damaged? Or what’s mutating in the virus?’ ” she said.

She will see the structural damage water treatments do to the virus — each component that is part of the virus being affected — in an attempt to find out how disinfectants do what they do to water-borne viruses.

Kelley grew up in Santa Maria, a small city in Brazil’s most southern state Rio Grande do Sul. It is much like Champaign-Urbana, Kelley says, because the Federal University of Santa Maria (UFSM) lies at the heart of the town, and much of the local economy revolves around it.

She inherits her love of science from both of her parents. Her father is a well-known scientist and professor at UFSM, and her mother is a biologist and high school and community college instructor. Sustainability has always been part of her home life.

“My mom was always very worried about the planet as a biologist. So we would get water from the rain and use it in our house,” she said. “We would try to make not so much trash, and we would try to recycle things,” she said.

In early 2015, she completed her undergraduate studies in a five-year Veterinary Medicine program — though her focus wasn’t on treating animals, but rather researching the viruses that made them sick. Her instruction in the microbiology side of medicine interested her most. She swapped time in animal hospitals for time in the lab to look for antibodies and viruses in samples from patients.

During her final year of undergraduate study, Kelley was required to complete an internship in a field of her choice. She chose the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, her father’s alma mater. Over a four month-long period she worked with her future lab partner Bernardo Vazquez Bravo on ultraviolet treatment of drinking water and with her now-adviser, Professor Joanna Shisler, on a cloning experiment with the skin disease-causing molluscum contagiosum virus (MCV). She applied to come back in the fall as a graduate student, specifically to work on the Smart Water Disinfection project.

“I am very excited about it,” she said. “I think I couldn’t be in a better project, honestly speaking. Sometimes in vet school, I was feeling kind of lost because it wasn’t something that motivated me as much. But being able to work with sustainability and water treatment and everything I was taught as a kid by my mom, I feel very lucky to be able to work on something like this — on something I am really passionate about.”

For Kelley, sustainability is a balance of using what you can get from nature but at the sametime not damaging it for future generations.

“Everyone should be worried about the planet,” she said. “Otherwise, if it’s just one in 1,000 people doing something, there is no way sustainability is achieved.”

She’s encouraged by the change she sees in businesses using sustainability features as marketing tools. A bandwagon for the environment is forming, and Kelley intends to be on it.

After completing her Ph.D., Kelley would love to be in a developing country implementing what she learns in the lab. There’s great potential for dialogue, she says.

“Most people have to worry about what to eat, let alone if they are using the most effective water disinfection. They don’t really care if the water has some byproducts from treatment so long as there’s water to drink.”

She hopes to bring the new wave of water disinfection technology to the people who need it most.

Return to Smart Water Disinfection Project page