Computer rendering of the front facade of 808 S. Lincoln Ave., which served as the base for Illinois’ 2016 Race to Zero competition retrofit design.

University of Illinois students from a variety of disciplines and backgrounds have learned to work together to make an impact beyond the classroom.

Through the U.S. Department of Energy’s annual Race to Zero competition, 22 Illinois undergraduate and grad students (representing seven different campus departments) collaborated on a design for a highly energy-efficient home. Much more important than the second-place finish among nine teams in the small multifamily housing category, these students are learning about different people and different disciplines — all for the good of solving a major challenge.

The Race to Zero competition presents a theoretical challenge to its participants: Design an affordable residence that operates on as little energy as possible. Participating teams submit detailed project proposals and supporting documentation for new construction or a retrofit of a single-family or multifamily residence. Although energy is the big buzzword, designs are awarded points in nine other categories in addition to energy performance, among them architectural design, interior design, building envelope (what separates inside from outside), and innovation. All categories are worth an equal number of points, making no one student’s area of expertise more important than anyone else’s.

Called the “LINKoln Locale Project,” the team’s 2016 contest entry proposed a deep retrofit of a real student apartment building owned by The University Group located at 808 S. Lincoln Ave., right across the street from student-favorite Caffe Paradiso and a Jimmy John’s location. The new proposal for the 1920s three-story building has eight rental units, featuring two, three or four bedrooms each.

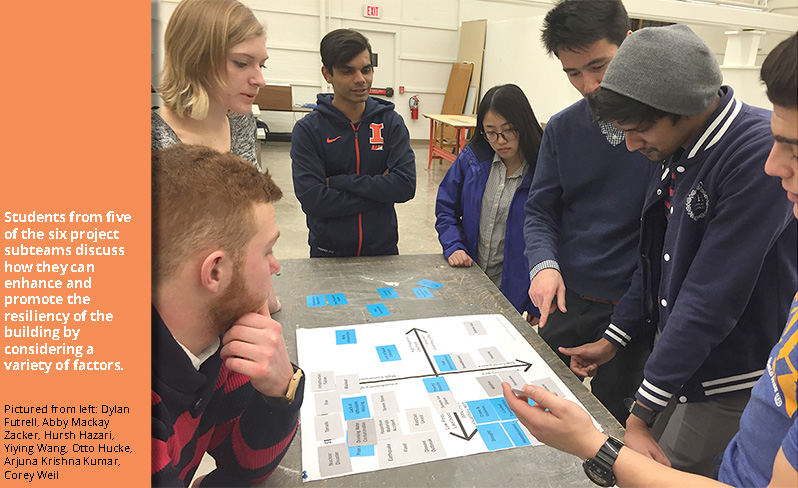

To transform this building into an ideal zero-energy residence, the large Illinois team subdivided into six working groups to tackle various aspects of energy efficiency: heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC), architecture, photovoltaic energy generation, water, lighting and appliances, and finance and construction.

Although the team was divided, the division actually made the students work together more closely, said Amir Amirzadeh, a Ph.D. student in Architecture and the Illinois Team Coordinator.

“We had so much collaboration. For example, if the architecture group designs the rooftop in such a way to fit a green space for residents, how does that affect the solar panel configuration? Same with the water team: If they use a certain kind of strategy to collect water on the roof, how does it affect the architectural layout?” he said.

“Together we learned a lot,” Amiarzadeh said, as members of different teams would look over each other’s work and offer feedback or ask questions about engineering decisions made.

“I’m in an architecture field, and when I look at my own work I might not catch something, but when someone from another mind-set looks at it, they might be able to add to it or refine it further,” Amirzadeh said. “That [collaboration] was a great opportunity for the entire team to see what other people in other fields think, and learn how they can contribute or develop upon someone else’s work.”

This collaborative atmosphere was responsible for some of the best design features that put the LINKoln Locale project toward the top of the list. Here’s just one example:

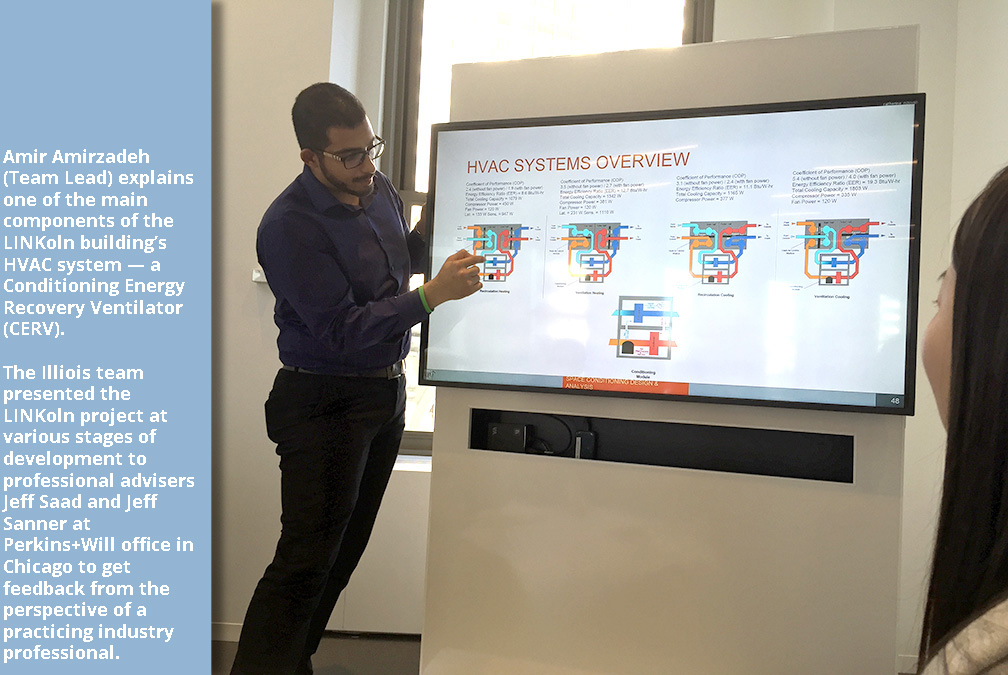

To provide heating, cooling, and air quality to the building, the LINKoln design used a Conditioning Energy Recovery Ventilator (CERV) mechanical system — an alternative form of traditional HVAC — designed by Illinois Mechanical Engineering Professor Ty Newell. Almost every member of the Race to Zero squad was involved in the selection and integration of this core building system. First, the HVAC group identified several options to provide heating and cooling. Then, the finance-focused group ran cost-benefit analyses to compare the energy efficiency, performance, and cost of several systems and offer a recommendation. The HVAC and energy generation groups worked together to make sure the CERV’s mechanical components and geothermal heat exchange components were compatible. At the same time, the architecture team worked closely with the HVAC team to allot sufficient space in the floor plan to accommodate final system parts, air delivery duct works, and placement of vents and intakes in each unit.

The Illinois Race to Zero delegation with their trophies from the 2016 competition. From left: Cory Mosiman, Amir Amirzadeh, Shuli Huang, and Architecture Associate Professor Ralph Hammann.

For Shuli Huang, a Master’s student from China in his first year in Mechanical Engineering, the prospect of doing something “for real” and with other students was a big draw to participate in Race to Zero.

“It’s more practical compared to my research studies, which are more front-end and innovative, and really quite difficult sometimes. In the process of doing this project, I had a lot of experiences with students in other departments, and they gave me a lot of other technologies and knowledge I will not learn in my other classes,” he said.

Huang was one of three students from Illinois to attend the competition’s final two-day event — the business pitch.

“I think it kind of broadens my eyes, especially going to the final event (in Colorado), you got to meet a lot of pioneers in this field, and see a lot of energy efficient houses. I met a lot of friends out there,” he said. He intends to stay in touch, especially with the other Chinese international students he may find himself working with one day. His experience is a perfect example of the Race to Zero competition’s main goals: to inspire and develop the next generation of residential design and construction professionals with building science expertise and a thirst for sustainability.

The importance of programs like Race to Zero in that effort of shaping the future cannot be overstated, Amirzadeh said.

“We have amazing opportunities here at our school, and we have wonderful resources in our school that are sometimes overlooked. Those wonderful resources are… our students who study here. Projects of this type are invaluable for many reasons. One is that it somehow teaches students how to work with each other when they aren’t from the same field. Another thing is [students] can develop something that is new: a product of a multidisciplinary group. It could help get your voice out.”

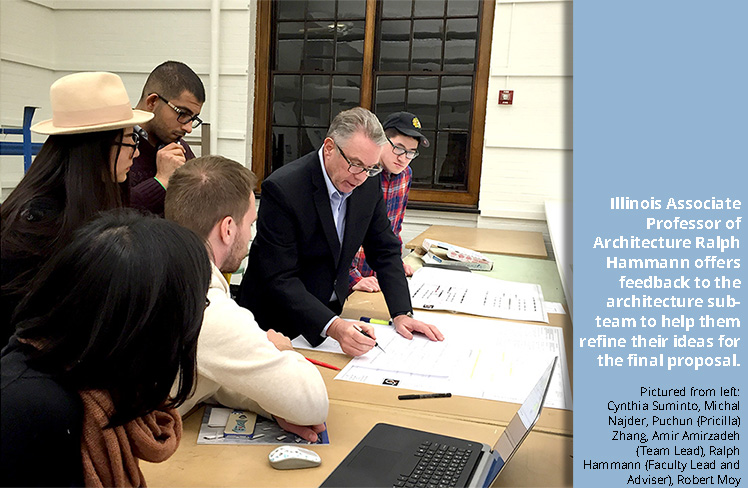

Race to Zero team members are selected through a campuswide open application process in early fall. The 2016 team was advised by Associate Professor Ralph E. Hammann, holder of the Thomas D. Hubbard Professorship in Architecture.

More information about the Race to Zero competition — including the Illinois team’s powerpoint presentation about the LINKoln Locale project — is available on the contest’s website. View a complete list of student members of the 2016 Race to Zero team.

All photos are shared courtesy of the Illinois Solar Decathlon 2016 Race to Zero team. Captions provided by Amir Amirzadeh.

— Olivia Harris, iSEE Communications Specialist